How to navigate a commodities multiverse…

“Commodity” is a strange word. It is derived from the Latin word commoditas, meaning roughly “advantage,” and came into English by way of the French commodité, meaning an amenity or convenience.

Technically, just about anything can be a commodity. Traditionally, the word “commodity” refers to any fungible economic unit, mostly specific physical resources, like coal or wheat. Today, just about everything under the sun has been commoditized, from physical objects to knowledge, and everything in between.

Even so, there is a subset of commodities that are different than the rest, namely, the essential building blocks of economic life. Indeed, one could tell the history of human civilization by tracing the types of commodities that assumed this importance at a given time in history – and how humans competed over access to them or transcended the need for them via scientific progress.

This became all the truer in the wake of the first Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century, as a unique combination of technological advances and cultural effervescence gave birth to modernity in all its splendor and horror. There were many reasons Great Britain turned into an empire, but one of the most important was its abundant supply of coal.

Enter the 20th century, and the importance of coal soon yielded to oil. (Daniel Yergin’s The Prize is a magnificent account of how this transition happened – and how the history of oil production defined much of 20th century geopolitical history.)

For the first time since the 1750s, the world seems to be moving away from hydrocarbons. Climate change – both the actual changes in the environment and the political narrative constructed about those changes – is leading many of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful nations to reimagine the relationship between human civilization, modernity, and the commodities essential to our future. The “commanding heights,” in Yergin’s parlance, are up for grabs.

That’s all well and good, but anyone can write a pithy article about commodities. Here, we must challenge ourselves to go deeper, namely: what are the commodities that will define the future of the world? How do you identify these commodities, and how can you successfully invest in this multiverse?

Obviously, we’re not going to provide you with the answers here. Instead, we’re going to take a step back and engage in some true, “blue-sky” thinking. To paraphrase what Socrates allegedly once said: “The beginning of knowledge is the recognition that you probably don’t know what you think you know.”

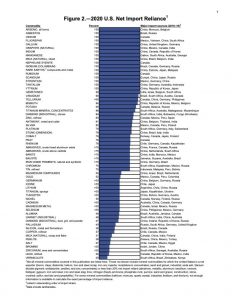

We are hardly alone in trying to identify the multiverse of commodities that will shape the future. In 2018, the U.S. government released a list of some 35 commodities that it identified as “vital to the Nation’s security and economic prosperity” and upon which the U.S. is “heavily reliant on imports.” The extent of U.S. dependence is summarized in the handy USGS graphic below.

Source: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021.pdf

Here’s a similar British Geological Survey list. Note that the British study is ranked in times of relative supply chain risk, as determined by a number of key variables, including production concentration, reserve distribution, recycling rate, substitutability, and political stability.

Source: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/download/statistics/risk_list_2015.pdf

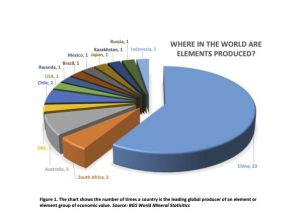

Here is another chart from that same report, one that identifies the countries where the world’s most important and endangered commodities are produced. We’ve already covered two of the top four in recent editions of the Strategic Perspective – the Democratic Republic of Congo (cobalt) and South Africa (manganese, platinum, chromium, and more).

Source: https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/download/statistics/risk_list_2015.pdf

These are as good a place to start as any, but as you can probably tell, they are also overwhelming. You can’t invest with a firehose, dousing every conceivable geopolitically scarce commodity you can find with capital, and expect to make out ahead of the game. One must temper the bounty of imagination with the rigors of analytical discipline.

There are some commodities that human beings will need no matter what is happening in the world. If aliens from a Jovian moon invade Earth, if global temperatures rise an apocalyptic 6 °C, if China and the U.S. beat their weapons into plowshares – there are a few commodities that will stand the test of time. Let’s start with three:

- Water

- Food

- Oil

Each of these commodities is a universe unto itself. From a supply standpoint, there is hardly a shortage of water in the world, quite the opposite. But as with many commodities crucial to human civilization, it’s all about where water is located. The Arab Spring began with a drought in Syria in 2008. The never-ending India-Pakistan rivalry is dressed up in religious garb and mutual enmity, but at its core is a water conflict. As water becomes scarcer in places like the Middle East, Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, this question will become even more pressing. The answer is likely not to own water, but rather to find the companies that are innovating with technology that eases the bottlenecks and helps make water less scarce.

Similarly, food is a universe unto itself. Coal powered the Industrial Revolution, but it was advances in making food production more plentiful and more predictable that led to the increases in human population that were a necessary precondition of the Industrial Revolution. Climate change is changing food production globally – and always has. Once, the Middle East was a cradle of civilization. Now it is mostly desert. Drought in South America has brought water levels at points on the all-important Paraná River to 15 centimeters. Phosphorus and potassium fertilizer supply chains are fraught with geopolitical risk, from Belarus to Morocco.

And then there’s oil. The world won’t be giving up on its most important hydrocarbon and fuel source overnight. Even as more countries transition to greater focus on renewables, like solar and wind, and even to nuclear, the need for good, old-fashioned oil, natural, gas, and even coal will remain. Indeed, that so many countries are transitioning away from hydrocarbons might make those industries less attractive…leading to still more scarcity of supply and driving prices up, as we’ve seen just this year.

Then there is a second tier of resources, the unseen “stuff” that is mined around the world that most of us have little direct relationship with. If you’re reading this on your phone, there’s probably lithium or cobalt in your device. Most of the world’s cobalt is in the DRC, and much of it is mined in abhorrent conditions. Lithium, of course, is also crucial to battery technology, as is graphite and nickel. As with water, for many of these critical commodities, there is enough to go around in theory – but in practice, supply is constrained by myriad factors, from geopolitical risk to the difficulty of mining these commodities directly.

And here’s the real kicker. If we are truly moving toward a world where renewables play a bigger, even *the* critical role in energy production…that is a Kuhn-ian paradigm shift if ever there was one. If humanity transitions from mining finite resources in the ground to capitalizing on ubiquitous resources that no single company or even country can own, what will that look like? And won’t the intense competition that has defined coal, oil, and other critical commodities simply get passed on to the second order commodities necessary to capture renewable energy? Perhaps the wisest investment is not in commodities themselves, but in the technologies being developed to change the commodity mix we are dependent on today.

To put the puzzle together, and to bring this opening salvo to a conclusion, let’s end by identifying a few key attributes that a commodity must have to be considered in our investment multiverse. It must be critical to one of three things: human life, modern industry, or cutting-edge technology. Demand must exceed supply, and there must be few, if any, viable substitutes, either now or on the horizon. They cannot be easily recycled, and supply (such as it is) should be concentrated in a small number of countries. Consider also whether the commodity in question is a byproduct of another.

Whatever survives this gauntlet is no mere commodité. It is a building block of the future, and as such, a tremendous opportunity. Only once you’ve distilled your list to the essentials can you begin to shift from strategy to tactics, i.e., long or short, commodities or equities, futures or physical property, technology or physical supply. But not a moment before you’ve done the macro-work, and never forgetting that the only guarantee about tomorrow is that it won’t look like today.