Reading the Steel Leaves

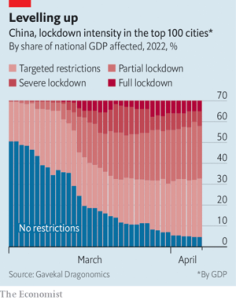

Most of the world has accepted that COVID-19 is going to be with us for a long time. Like the flu, COVID-19 is now simply an endemic virus; there is no putting the sniffly genie back in the bottle. The lone holdout is China, where President Xi Jinping has made “COVID zero” not just the Chinese Communist Party’s policy, but his own signature measure “swept down from the commanding heights.” While in the U.S. even the government is insisting the country is “out of coronavirus pandemic phase,” China is locking down entire cities. Shanghai has been shuttered for over a month, and only in recent days have there been signs that it is ready to ease lockdowns. Beijing, it seems, may be next.

Source: https://www.economist.com/china/2022/04/16/the-way-chinese-think-about-covid-19-is-changing

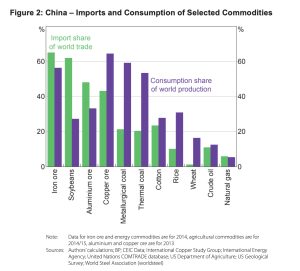

Cue the doomsday prognosticators, who think China’s heavy-handed response will lead to revolution, or starvation, or worse. It has certainly led to a swoon for Chinese equities, and for commodity prices generally, which until just recently seemed caught in a doom-loop of their own due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the prospect that energy and agricultural exports from both will disappear from global markets. Such is the extent of the influence China still exerts over the global economy. For things like coal, metals, and pork, China still accounts for half of global consumption. A true Chinese industrial shutdown would be the opposite sort of crisis: a collapse in demand for commodities and supply chain disruptions galore.

It is at times like these that is good to remember a pithy quote from the American author F. Scott Fitzgerald: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Most of the media is telling one story about China – about its lockdowns, about how Shanghai is “furious,” about how Xi is casting about for someone to blame. This is a part of the story, to be sure, and it is particularly true for foreign firms and expats in China. But there is another side to the story, namely, that the Chinese government is not sitting on its hands. On the contrary, it looks like it is about to go all out in supporting the Chinese economy.

Consider that just a few weeks ago, Premier Li Keqiang told a meeting of the Chinese State Council that the government felt a “sense of urgency” to adopt stronger economic policies to support the economy. Yes, the People’s Bank of China didn’t cut interest rates as was expected – but the extent of the policies rolled out by the PBoC was similar to the initial measures China imposed in early 2020. On the PBoC’s list of 23 measures to support the economy are encouraging financial institutions to support local government infrastructure projects, expanding the relending quota for small businesses and agricultural businesses, deferring mortgage payments, buying more coal, and making it easier for companies to borrow from overseas, among others.

When that turned out to be insufficient, Xi kept on coming. At the end of April, he chaired a meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs and emphasized two main objectives: strengthening construction of infrastructure, to include energy, ports and water ways, transportation, and network-based infrastructure, and strengthening the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee over economic work. Translation: China is going to build a lot of infrastructure because the Chinese Communist Party said so.

A few days later, Caixin reported that China’s financial regulators want state-owned asset management companies (AMCs) to work with as many as a dozen Chinese real estate developers, including China Evergrande Group, to avert a potential collapse. Regulators also have directed Chinese banks to ensure financing for the real estate sector is kept stable and orderly. This is a hugely significant about-face from Xi, who has seemed content to let greedy property developers fail since Evergrande’s problems became apparent in September 2021. After all, Xi had insisted property developers curb speculation in 2018, and it was their fault for not kowtowing.

That was all well and good before the Russia-Ukraine war and the COVID-19 resurgence in China, but things have changed in just a few short months. Now, it is more important to Xi support economic growth and prop up those real estate developers even if it means sweeping their debts under the rug.

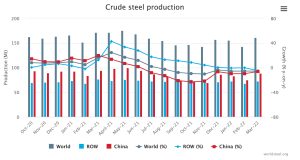

As a result, even as panicked Beijing residents stockpiled food and supplies, China was lifting restrictions in places like Tangshan city, a key hub for Chinese steel-making. China’s daily coal output is marking new record highs – a sign of increased demand for energy. China’s top chip maker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC), has two-thirds of its workers literally sleeping in the factory. One day, iron ore futures are free fall – the next they are surging on promises of Chinese support. Australian firm Fortescue is raising its export targets and indicating China’s demand and utilization rates are steady.

Indeed, despite previously stated Chinese government goals to reduce steel production, steel production has actually risen considerably in China from November 2021, when we wrote on the prospect for iron ore prices in the year ahead. (Click here if you missed it.) In that piece, we noted that China was going to consume less iron ore, iron, steel, copper, and other commodities due to its desire to support “stable growth.” What Xi and the CPC have said in the last week or two is that it is changing its policy priorities. Publicly, the Chinese government is saying its zero COVID policy is about “people first, life first.” What the Chinese government is actually doing however is not just about lockdowns – it bears resemblance to similar moments in 2008, 2015, and 2020, when the need to support growth came first above all else.

There are still a lot of uncertainties here – especially unknown unknowns. The key point to remember is that when it comes to inflation, the biggest global player isn’t the Federal Reserve, or the Bank of Japan, or the various monetary policies of emerging market economies. It is still China. As politically frustrating as that may be for many reading this, the fundamental reality is that the world is still addicted to Chinese growth. We leave the politics to others, and instead can only offer this sobering point: That as long as China is such an important part of the global economy, understanding whether China is shutting down or gearing up for an infrastructure binge is of crucial importance – as is keeping one’s mind open to the possibility of Beijing having the gall to attempt both at the same time.