THE EUROPEAN ENIGMA

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” – Winston Churchill, 1 October 1939

You have likely heard at least part of this quotation before – the bit about “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” (Just do a quick Google news search to see how often and diversely that clause is bastardized from its original context.) It is an exceedingly pithy turn of phrase, to be sure, but ironically, focusing on the pith only serves to miss the point.

Churchill was actually saying that Russia was eminently understandable, provided one could identify its national interest. A rare moment of Churchillian modesty – “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia” – is quickly resolved in harmonious self-assurance. Churchill solved the riddle wrapped in the mystery inside of the enigma. He identified Russia’s national interest and was able to predict the very thing he said he could not forecast. That is the moral of the story.

Today, the biggest macro riddle/mystery/enigma to solve on the world stage is not Russia, the U.S., or even China for that matter. To be sure, predicting the future of any country in the long-term is not easy – which is precisely why the future of that great sleeping geopolitical behemoth, the European Union, is so hard to do. The EU is a collection of 27 member states, a half-sovereign entity living in geopolitical purgatory: too weak to behave like a state, and yet too strong to be considered just a free trade bloc.

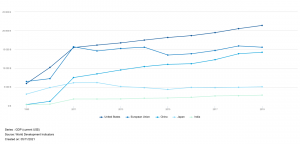

The European Union’s incoherence belies its importance to the global economy. Indeed, from 2007-2009, the EU was actually the largest economy in the world in terms of GDP, narrowly outstripping the U.S. In the years since, the EU has gone from crisis to crisis: Greek sovereign debt, migration, and then Brexit followed in quick succession. On the one hand, despite the instability, the EU remains the second largest economy in the world. On the other hand, the EU has clearly stagnated. While the Chinese economy has doubled since 2010, the EU economy has barely grown.

GDP (Current USD) in the U.S., EU, China, Japan, and India

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US-EU-CN-JP-IN

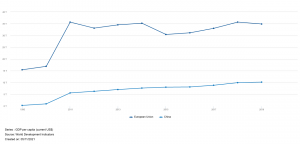

Of course, things are never quite that simple, or even as they seem. As a bloc, the EU is still a force to be reckoned with. But there is a great deal of inequality within the EU as well. There are any number of statistical indicators with which to make that point, but let’s just use simple GDP per capita to demonstrate how far China has to go before it can supplant the EU as an economic power.

GDP Per capita China v. EU

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=EU-CN

Here, however, is a map showing GDP per capita within the EU itself. As a whole, the EU is very rich, but dive a little deeper, and there is tremendous inequality within the bloc. To put the map in some perspective – Romania and Bulgaria have GDP per capita’s relatively close to China’s.

EU GDP Per Capita by State

The question, then, is whether the European Union can become more than the sum of its parts. The 2010s weren’t exactly a ringing endorsement for the EU, which always seemed to be on the brink of being torn apart. But COVID-19 offered the bloc a distinct opportunity: a chance to fix the EU’s original sin and forge a more coherent and integrated political, economic, and even security framework. Within two months of the pandemic’s outbreak in Europe, Germany and France joined forces to try and reshape the EU into a more sovereign entity capable of meeting the challenges of an increasingly multipolar world.

To be sure, the results so far have been mixed. The EU’s Next Generation COVID-19 recovery plan – the plan that entails the European Commission borrowing almost €750 billion as a unified bloc for the first time in its history – has been mired in delays and bureaucratic red tape. The pandemic might well be over by the time all the t’s are crossed and the i’s dotted at this rate. Meanwhile, Hungary and Poland continue to be a thorn on the EU’s side – Hungary in particular. Just this week, an uncharacteristically angry Germany lashed out against Hungary for blocking an EU statement criticizing China for what is happening in Hong Kong.

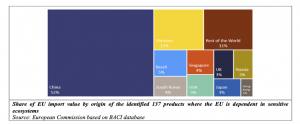

But there is a glass half full perspective to consider here as well. Last week, the European Union unveiled a bold new update to its 2020 Industrial Strategy. The document identifies 137 products, representing 6 percent of the EU’s total import value of goods, upon which the EU is dependent on foreign sources. The list includes components and materials critical to green energy, healthcare, and digital transformation. Here is a chart from the report showing exactly who the EU is dependent on – i.e., from whom the EU is about to throw its full weight to wean itself.

Share of EU Import Value for Critically Dependent Products by Origin

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-new-industrial-strategy.pdf

Or consider that 14 EU countries are reportedly going to try and stand up a new rapid response military response force of some 5,000 soldiers that could “help democratic foreign governments needing urgent help.” Ignore the ideological veneer – this is no less than the EU attempting to create an indigenous, explicitly European force capable of defending European interests. Skeptics will sneer that 5,000 troops are nothing, and they are right to sneer – but more thoughtful observers should wonder whether this is a nascent sign that something is truly changing within at least some of the EU community.

At the end of the day, the European question boils down to the same variable as Churchill’s Russian problem. What is Europe’s national interest? (An addendum may be necessary to the question in the EU’s case: Does the EU even have a national interest to begin with?) Upon that answer rests the fate of the entire project, and with it, the geopolitical balance of power and the global macroeconomic landscape.

There are multiple possible scenarios, of course. French President Emmanuel Macron has been pushing for a so-called “multispeed” Europe since taking up residence in the Élysée in 2017. Macron envisions a smaller concentric circle within the EU willing to do what is necessary to protect the EU’s interests even as other less willing countries remain in the EU’s general orbit. Alternatively, the EU may get so frustrated with obstructionist forces like Hungary that it decides to make a political example of a European malcontent, including potentially suspending it from the bloc. Perhaps Brexit was not a one-off, and more defections from the bloc are imminent. A full-scale implosion is not especially likely – but it’s also not impossible.

It is hard to overstate how important this question is from a macro perspective. Necessity is the mother of invention, as the aphorism goes, but put slightly differently and in terms more befitting The Strategic Funds’ overall approach, necessity breeds innovation, which in turn generates growth and opportunity. If the EU’s national interest, and that of its member states, is to remain a globally significant economic and political force, then the Next Generation EU Recovery Plan is just the beginning, and Brussels will collect billions, if not trillions, of euros from its member states to bulk up for the challenges to come.

If Brussels fails, and the EU really is a castle made of sand, the opportunity will of course be different but no less important, situated more in Europe’s great capitals rather than in Brussels. It is not a coincidence that previous moments of the industrial revolution were also periods of tremendous economic growth, political transformation, and social upheaval. As the world passes through another industrial transfiguration, take some time and consider the riddle, mystery, and enigma of the EU’s future: whether to devolve into national self-competition once more or to transcend its past and become the continental power Churchill himself imagined at the University of Zurich in 1946: a United States of Europe.

Meet the Author:

Mr. Jacob L. Shapiro

Global Macro Adviser

Jacob L. Shapiro is a geopolitical analyst with over 10 years of experience providing clients with the context, foresight, and extensive analysis they need to solve for the unknown and enhance their understanding of global and regional affairs. He is the founder and chief strategist of Perch Perspectives, a human-centric business and political consulting firm that applies geopolitical expertise to business strategy for Fortune 500 companies and governments. Formerly, he was the director of analysis at Geopolitical Futures and a Middle East analyst at the global intelligence firm Stratfor. A loyal student of history and geography, Jacob wields both in order to empower his clients to make accurate, informed decisions and gain a more holistic view of the events and issues that impact them. Jacob always maintains a distinctly global focus in his work, but he also has extensive experience tackling problems in the supply chain, agriculture, technology, and energy markets.

Disclaimer

This piece (Strategic Thoughts) does not constitute an offer to sell, solicit, or recommend any security or other product or service by Strategic Capital Advisors or any other third party regardless of whether such security, product or service is referenced. Furthermore, nothing in this piece is intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice nor should it be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any investment or security or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction.